- Home

- Frank X. Walker

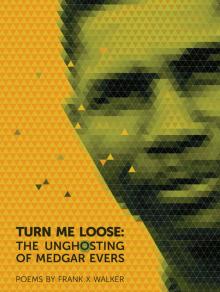

Turn Me Loose

Turn Me Loose Read online

Turn Me Loose

Turn Me Loose

THE UNGHOSTING OF MEDGAR EVERS

Poems By

Frank X Walker

Published by The University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

©2013 by Frank X Walker

All rights reserved

Designed by Kaelin Chappell Broaddus

Set in 10/14 Century Old Style

Manufactured by Sheridan Books

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for

permanence and durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America

13 14 15 16 17 P 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Walker, Frank X., 1961–

[Poems. Selections]

Turn me loose : the unghosting of Medgar Evers :

poems / by Frank X. Walker.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-4541-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8203-4541-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Evers, Medgar Wiley, 1925–1963—Poetry.

2. United States-—Race relations—Poetry. I. Title.

PS3623.A359T87 2013

811′.6–dc23

2012046531

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN for digital edition: 978-0-8203-4586-4

Dedicated to the

Mississippi Truth Project

and the invisible army

of soldiers for justice

whose names might

never be spoken.

If I die, it will be in a good cause.

I’ve been fighting for America just

as much as the soldiers in Vietnam.

I do not believe in violence either by

whites or Negroes. That is why I am

working tirelessly with the NAACP in

a peaceful struggle for justice.

—MEDGAR EVERS

When I go to Hades, I’m going to raise

hell all over Hades till I get to the white

section. For the next 15 years we here

in Mississippi are going to have to do

a lot of shooting to protect our wives

and children from a lot of bad niggers.

—BYRON DE LA BECKWITH

Contents

FOREWORD

How Do We Comply?:

Answering the Call of Medgar Evers

Michelle S. Hite

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

PART I DIXIE SUITE

What Kills Me

Ambiguity over the Confederate Flag

Rotten Fruit

Humor Me

The N-Word

Southern Sports

Byron De La Beckwith Dreaming I

I’d Wish I Was in Dixie Too

PART II SOUTHERN DREAMS

Fire Proof

Listening to Music

Life Apes Art Apes Life: Byron De La Beckwith Reflects on Birth of a Nation

White of Way

Music, Niggers & Jews

Swamp Thing

Stand by Your Man

Husbandry

Unwritten Rules for Young Black Boys Wanting to Live in Mississippi Long Enough to Become Men

PART III LOOK AWAY, LOOK AWAY …

Byron De La Beckwith Dreaming II

After Dinner in Money, Mississippi

World War Too

Believing in Hymn

Southern Bells

Fighting Extinction

Harriet Tubman as Villain: A Ghost Story

Legal Lynching

After the FBI Searched the Bayou

Haiku for Emmett Till

No More Fear

When Death Moved In

PART IV GALLANT SOUTH

Byron De La Beckwith Dreaming III

After Birth

Sorority Meeting

One-Third of 180 Grams of Lead

Arlington

Cross-Examination

Bighearted

Anatomy of Hate

What They Call Irony

On Moving to California

PART V BITTER FRUIT

One Mississippi, Two Mississippis

A Final Accounting

Now One Wants to Be President

Epiphany

Last Meal Haiku

White Knights

Evers Family Secret Recipe

The Assurance Man

Gift of Time

Heavy Wait

TIME LINE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Foreword

HOW DO WE COMPLY?

ANSWERING THE CALL OF MEDGAR EVERS

Kentucky assumes a prominent place in Frank X Walker’s five previous poetry collections. Affrilachia (2000) was his first collection and serves as the defining text of black life and experience in the Blue-grass State. Black Box: Poems (2006) extends Walker’s voice and vision of the overlooked lives of black people in Kentucky through a consideration of his own Affrilachian life. Walker’s persona poems keenly focus the issues of racial subjectivity and place through the embodied narratives of black subjects with deep Kentucky ties. Buffalo Dance: The Journey of York (2004) and When Winter Come: The Ascension of York (2008) imagined what life might have been like for York, the lone black man on the Lewis and Clark expedition. York had been enslaved in Louisville, Kentucky, and served as William Clark’s body servant. Walker also eloquently lays to rest Kentucky native Isaac Murphy through a graceful imagining of his inner life and a careful crafting of the lives of his dear ones in Isaac Murphy: I Dedicate This Ride (2010). Turn Me Loose: The Unghosting of Medgar Evers, Walker’s most recent collection, turns toward a deeper South, but not away from the subject of the overlooked lives of black people who make up life there.

By most accounts, Medgar Evers’s contributions to the modern day civil rights movement have been overlooked if not forgotten in chronicles of the movement and so from modern memory.1 These poems masterfully confront this erasure through an engagement with Evers’s prominence in the inner workings of white supremacist identity and its manifestation as violence in both formal and informal practices of segregation. This collection underscores the startling incongruity of this contemporary elision given the prominence Evers held as a contestant to the order of white supremacy. To this end, Evers was all but invisible and marginal to assassin Byron De La Beckwith or to the White Citizens Council, the Ku Klux Klan, Governor Ross Barnett, and the Mississippi police. This meant that Evers was also all but invisible as a figure for every black person who dared to challenge formal Jim Crow laws and “Dixie decorum,” which Walker’s poems identify as those unwritten rules wherein black people publicly acknowledged their inferiority before whites.

Walker beautifully sets in relief the ways that Medgar Evers’s singular life symbolizes black life in Mississippi. These poems create an intimate portrait of what it must have been like for people to live amid state-sanctioned loathing; the effort that must have been required to recover dignity from relentless efforts to infuse indignity into the meaningfulness of blackness, from constantly deflecting racist blows. Walker’s consideration of the life and cold-blooded assassination of Evers dramatizes the daily horror of dehumanization that thoroughly sought out every corner of southern existence in an effort to degrade the quality of black life and reduce its quantity to prove this point. Indeed, the specter of Evers proves seriousness of purpose in maintaining white supremacy in the segregated South, especially in Mississippi.

Mississippi could create Halloween in August, memorably making a monstrous mask of young Emmett Till’s face eight years before Alabama made ghouls of four little Sunday school girls in September. Mississippi muted the voices of its black majority by denying whole counties of black citizens the right to vote, at the same time amplifying the cry of one black woman whose “Mississippi appendectomy” gave involuntary sterilization its name. Mississippi amplified the voice of a governor whose ardent love for segregation ignited the passions of a crowd sympathetic to blocking one black student’s admittance into law school at Ole Miss and set the symbolic bar for an Alabama governor’s stand in another schoolhouse door.2

Walker’s poems paint a vivid picture of Mississippi macabre but also of the elegance that black people made of life there. Such elegance gets imagined just as I remember observing it in my own Affrilachian life. I knew and saw black people who could be quiet together; who when alone could think sweetly or soberly about the other; who enjoyed one another with careful measure; who nurtured one another; who not only slept together but rested together. I believe the persona that Walker ascribes to Myrlie Evers, who conjures sweet memories when the smooth sound of Motown plays in her ear. I see the children she lays down to bed and the dreams she nurtures in a place that insists she does not belong. I admire the hope she continues to sustain and the arguments she continues to make for love.

These poems perform. You not only see the drama unfold but you hear the way that Walker scores it. Music can be heard throughout this work. You not only hear it in reading the epigraphs but also through the interpretative acoustics of the surprising fusion of voices throughout. The opening epigraphs featuring the one instance where Medgar Evers speaks set against the voice of Byron De La Beckwith marvelously frame the “divergent points of view” that Walker identifies in his introduction. Having these two men’s words together on the same page reflects the stark differences between points of entry and perspectives on living well in Mississippi. Walker offers his work as an “interruption of the silence” concerning Evers’s erasure as a civil rights legend and thus serves as an attempt to address an important oversight in a long and terrible legacy of southern violence. This interruption comes to figure reconciliation and possibly healing from the catastrophic wounding that is marked specifically by the assassination of Evers but that also exceeds his ghost. His final words, “turn me loose,” were an address to history, but his ghost highlights the liveliness of history. Thus, the title, the epigraphs, and the introduction establish the enormity of this project, which I see as the hard work of reconciliation in light of the nature of the wound and given the absurdity of its situatedness in southern history. Walker brings this point to sonic resonance most profoundly through his thoughtful treatment of “Dixie” and “Strange Fruit.”

The section headings “Dixie Suite,” “Look Away, Look Away …,” “Gallant South,” and “Bitter Fruit” reference “Dixie” or “Strange Fruit” respectively. The “Dixie Suite” captures the vast gulf between stark racial impressions of southern life measured by reactions to the song. Amid disputes over the true origin of the song’s creation, Mount Vernon, Ohio, native Daniel Decatur Emmett is credited with writing the song.3 Emmett penned the song as a member of Bryant’s Minstrels. “Dixie” assumed its gravity with the onset of the Civil War, when it became the adopted anthem of the Confederacy, and it held its seriousness of purpose when northern and southern bands composed versions of it that were performed throughout the war. While many versions of “Dixie” exist, the voice of the enslaved longing to return to plantation life has endured. Backbreaking and unremitting, unremunerated work gets imagined as tranquil longing through the laboring body of an enslaved person. For those who symbolize those laboring bodies, nostalgia for such a past and pride in this imagined South offends historical recognition of the toll of the historical South upon their lives.

Like jazz artist Rene Marie, “Turn Me Loose” aestheticizes an unlikely entanglement, creating a beautiful ambivalence that invests “Dixie” with new meaning.4 “Look Away, Look Away …” as a section title brilliantly raises an ethical question regarding bearing witness. It asks: to what extent can looking away align with loyalty? In the final section of “On Collective Memory,” Maurice Halbwachs posits that sometimes looking away offers us our only chance at loyalty.5 He reads Peter’s betrayal of Christ as just such a moment. Halbwachs reasonably asserts that when someone we love is about to experience something brutal or horrific, our impulse is not to stare or to be consumed with longing looks; instead, our impulse leads us to look away. Halbwachs contends that from this perspective, Peter had to turn away from Jesus, who was like a brother to him. Thus, in order for Peter to serve as a witness for Christ, he had to deny their brotherhood.

The poems in the section “Look Away, Look Away …” imagine the making of Evers into the NAACP field secretary who would become the necessary witness to the “strange and bitter crop” produced in his own backyard. Evers’s witness identified his steadfast loyalty to the lives of those who, according to Abel Meeropol, were the by-products of a macabre southern ecology. Under the pen name Lewis Allen, Meeropol wrote a poem, “Bitter Fruit,” that would become the lyric of the song “Strange Fruit” in 1939 as an indictment of lynching as a natural feature of the South.6 In the song, lynching, an extralegal, vigilante practice of killing mostly black people through burning, mutilation, and hanging, serves as an environmental, regional, and racial indictment of a grisly southern tradition made to look like an ecological norm. Where “Dixie” celebrates, “Strange Fruit” indicts.

Though Evers was brutally murdered, much like the victims whose stories he recorded, historian Taylor Branch notes that the killing of Evers was not referred to as a lynching but an assassination. Thus, “the murder of Medgar Evers changed the language of race in American mass culture overnight,” according to Branch.7 Walker acknowledges this difference through the way that he deconstructs the song’s text to rethink Evers’s legacy. The “Gallant South,” taken from the first line of the second stanza of “Strange Fruit” emphasizes various spectacles and spectral scenes that extend the singular startling, grisly one. Through this broadened lens, the scope of violence opens to reveal other, more anesthetized forms of violence usually hidden behind other, more visible forms of brutality. Walker reveals the way that violence looks in dreams; the way it can inform how you imagine love; how it can transform lives and makes for unlikely unions. The voice of Myrlie Evers comes to stand for the living possibility of a “gallant South” as she converts the Willie and Thelma De La Beckwith cabal into a sisterhood in which her life intertwines with theirs.

The final section of Turn Me Loose, “Bitter Fruit,” cites the original title of the poem that would become “Strange Fruit.” Such a return becomes an act of remembrance much like the act necessary to answer the call of Medgar Evers. If we are to finally lay him to rest, to satisfy his request to turn him loose, we must remember. This remembrance, however, eschews the wistful recollection of a magnolia-scented South and embraces memories of the flowery scent mixed with the stench of roasting flesh. Compliance requires the recollection of putrescent truths. This remembrance would involve recognizing the on-going presence of the past in the brutal killing of James Craig Anderson. We will have complied with Medgar Evers’s request to turn him loose when we bring all of our creative powers to bear on questioning the return of the past. Frank X Walker’s collection of poems offers a worthy model for how we can deploy the imagination in service to the urgent call of history.

Michelle S. Hite

SPELMAN COLLEGE

NOTES

1. See Manning Marable, “A Servant-Leader of the People: Medgar Wiley Evers (1925–1963),” in The Autobiography of Medgar Evers: A Hero’s Life and Legacy Revealed through His Writings, Letters, and Speeches, ed. Myrlie Evers-Williams and Manning Marable (New York: Basic Books, 2005); Adam Nossiter, Of Long Memory: Mississippi and the Murder of Medgar Evers (Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo P

ress, 2002).

2. See Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954–63 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998); Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–64 (New York: Touchstone, 1999); John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995); Chana Kai Lee, For Freedom’s Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000); Spike Lee, 4 Little Girls (HBO Home Video, 2001); Christopher Metress, The Lynching of Emmett Till: A Documentary Narrative (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002); Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (New York: Pantheon Books, 1997); Stephen J. Whitfield, A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991).

3. See Howard L. Sacks and Judith Rose Sacks, Way Up North in Dixie: A Black Family’s Claim to the Confederate Anthem (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993).

4. See René Marie, Voice of My Beautiful Country (Motéma, 2011).

5. Maurice Halbwachs, “The Legendary Topography of the Gospels in the Holy Land,” part 2 in On Collective Memory, trans. and ed. Lewis Coser, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

6. See David Margolick, Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song (New York: The Ecco Press, 2001).

7. Branch, Pillar of Fire, 108.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following publications, in which earlier versions of some of the poems were first published:

The Active Voice: “Last Meal”

Black Magnolia Literary Journal: “After Birth,” “Arlington,” “Beckwith Dreaming III,” “Believing in Hymn,” “Evers Family Secret Recipe,” “Homecoming,” “Southern Girls”

Crab Orchard Review: “Rotten Fruit”

Iron Mountain Review: “Ambivalence over the Confederate Flag,” “Fire Proof,” “Listening to Music,” “Music, Niggers & Jews,” “On Moving to California,” “Now One Wants to Be President”

Turn Me Loose

Turn Me Loose When Winter Come

When Winter Come